Probably all baseball and softball players-everybody from Little League to Major League-would like to improve their hitting distances. Wouldn't it be great to slam a ball across the outfield every time you stepped up to bat?

So what are you going to do to give the ball more launch the next time you're up to bat?

On June 3, 2003, Sammy Sosa, the great Chicago Cubs hitter, was caught with some cork imbedded in one of his bats. The point of that, of course, is to make the bat lighter so that the player can get it around faster to the ball.

Sosa, who's hit more than 500 home runs during his years in Major League Baseball and is certain to become a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame when he retires, said he accidentally grabbed a bat he used to put on home run displays for fans during batting practice, and mistakenly used it during a game against the Tampa Bay Devil Rays.

Sosa was suspended for seven games, but, the lesson is that cheating is an unacceptable method of improving your runs-batted-in record.

In this section, we'll explore the basic physics of baseball, and try to figure out a way for you to hit more home runs for your team-without resorting to stuffing cork into your bat.

So What Seems to Be the Problem?

The problem that you'll attempt to solve during the course of this science fair project is how you can hit more home runs in your baseball games.

Before you start, though, there are a couple of basic premises that you need to understand.

The first is that, in order to do well at most activities, you need to practice correctly, and spend a lot of time perfecting your technique. This pertains not only to baseball, but all activities, such as ballet, baton twirling, singing, piano playing, basketball, and golf just to name a few.

Even really great natural athletes need to train and practice in order to be the best.

The second fact you need to keep in mind is that starting an activity at a very young age gives you a huge advantage over those who wait until they're older to begin.

When you're young, your brain develops neurological pathways that help your body to engage more easily in an activity, such as baseball. After a time, your brain and body know exactly what to do when a ball comes across the plate, or when you need to snag a quick out at first. Your body reacts reflexively, without having to wait for your brain to tell it what to do.

The game becomes almost an automatic routine. Your body doesn't have to think much about hitting the baseball, it just does it.

Most people develop these neurological pathways with everyday activities, like walking. You had to learn how to walk, just like you had to learn how to play the guitar or play tennis. Once you learned, walking became second nature. You probably don't need to think about how to walk-you just do it.

Motor skills, which are learned physical movements, are driven by long-established patterns in the brain. Once you learn to walk, walking becomes an established pattern. Same goes with hitting a baseball.

If you wait until you're 30 to start learning to hit a baseball, or a golf ball, or whatever, you're at a disadvantage. That's because your brain won't accept the pathways that make the game second nature as easily or as well as a younger brain. To be great at baseball, the motor skills should have been set in place a long time ago.

If you haven't been playing intense baseball since the time you were four or five years old, however, don't despair. By learning and applying a little physics to your game (along with a little work on your part), you can help achieve a more automatic response when the ball comes across the plate to you. Sorry about this, but if you're just starting a sport at the middle school or high school level, you won't ever have the speed and reflexes of an athlete who's been playing that sport since he or she was five or six. The pathways just don't form as well or as quickly when you're a teenager as they do earlier in life.

You'll probably never hit as many home runs as Sammy Sosa, but you can improve your game and increase your chances of knocking the ball over the fence.

If you want to, you can use the name of this section, "How Can You Use Physics to Become a Better Hitter?" as the title for your science fair project.

Or you could use one of the titles suggested below.

- Improving Your Chances of Hitting a Home Run

- What Do You Need: A Bigger Bat, or a Faster Bat?

What's the Point?

The point of this project is to help you understand the physical and mathematical mechanics of hitting a home run.

What's necessary in order for you to hit a ball absolutely as far as you can? One thing is a good pitch. The other is energy. A lot of energy.

When you hit a baseball, energy is literally transferred through the bat to the ball. The more energy contained in the bat, the farther the baseball will go.

The official scientific equation for this concept of energy is written below.

- Energy = 1/2 times the mass of the bat times the velocity of the bat (speed in a specific direction) squared

Or more simply:

- E = 0.5 mv2

So what does this mean to you and your baseball team? The first part of the equation tells you that if you increase the mass of the bat, the bat will potentially have more energy. The heavier the bat is, the farther the ball should travel.

The trouble with that is, if you've had experience with baseball, you know that swinging a heavy bat isn't the easiest task, let alone swinging it quickly. So what do you do?

Fortunately, increasing the mass of the bat is only one way you can increase the energy with which you hit the ball. You also can learn to swing the bat faster. If you check out the equation again, you'll notice that the velocity is squared. That means that doubling the speed at which you swing the bat results in a fourfold increase in energy. In other words, it gives you a lot more bang for your buck.

To better understand this equation, we'll analyze it by varying the weight of the bat and the speed of the swing.

Let's say that your bat weighs 32 ounces, and the speed of your swing is 50 feet per second.

With a 32-ounce (two-pound) bat and a 50-feet-per-second swing, the equation reads like this:

- E = (0.5 ) (2 pounds) (50ft/sec)2 = 2,500 units of energy applied to the ball

Now look at the equation when we've doubled the weight of the bat, while keeping the speed of the swing the same:

- E = (0.5) (4 pounds) (50ft/sec)2 = 5,000 units of energy applied to ball

Hang in there, now, this is almost over. The last way we'll look at the equation is to go back to the original 2-pound bat, but we'll double the speed of your swing:

- E = (0.5) (2 pounds) (100ft/sec)2 = 10,000 units of energy applied to ball

The equation clearly shows that doubling the speed of your swing is a much more effective means of improving your chances of hitting a home run than doubling the size of your bat.

Because the velocity is squared, but the mass isn't, you get considerably more energy applied to the ball by increasing the speed of your swing.

The challenge you face by doing this science fair project is to test whether you can increase both your strength and the speed of your swing, resulting in better hitting.

What Do You Think Will Happen?

If you're able to apply the concepts necessary to hit a home run, then you can hit the ball farther and improve your batting average.

You'll need to practice swinging the bat faster in order to increase the distance you're able to hit the ball. Of course, you'll also need to make contact with the ball. The fastest swing in the world isn't much good unless its energy gets transferred to the ball.

Don't worry, though. As you repeat the movements of swinging faster and hitting the ball, your brain pathways will help these motions to become more reflexive and automatic for you. It won't happen as quickly as it might have when you were five or six, but you'll see a big difference.

A major league pitcher having a good day can fire a ball over the plate in just half a second. Clearly, that leaves little time for the batter to decide on and execute a swing.Professional baseball players use their strength and their speed to try to hit the ball consistently, and to hit it far. A stronger player can use a heavier bat and still swing faster than a player who isn't as muscular. Those players who aren't as strong need to use a lighter bat and concentrate on swinging it as fast as they can.

Most major league players get a hit only once out of every four times at bat. So don't feel bad if you're not hitting home -runs every time you're at the plate.

Practicing batting will help you to increase the speed at which you swing. Working out with weights will increase your strength. Those two things, combined, will make a big difference in the amount of energy you get behind the ball.

For this experiment, you'll practice batting every day, and lift weights a couple of times a week. You'll need access once a week for eight weeks to a batting facility with an automatic pitching machine and a device that measures the speed at which you hit the ball. The speed of your hit will indicate whether or not you're increasing the amount of energy you're transferring from the bat to the ball.

Don't start lifting weights if you don't know what you're doing. Lifting weights that are too heavy or using improper technique can cause injury.

If you can get to such a facility more often than once a week, that's fine. If not, however, an outdoor batting area will suffice on the days you don't have to measure your speed.

You'll also need access to some weights. If possible, work with the trainer at your school or a professional at a gym to help you set up a lifting schedule that's right for you.

Most schools have weight rooms that are open to students at certain times. You'll need to lift weights two or three times a week and practice your swing daily in order to increase your muscle mass and improve your speed.

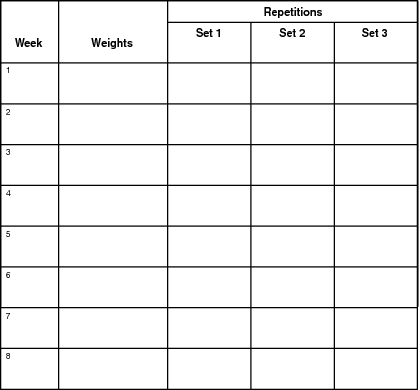

Keep track of how much you're lifting, and the number of repetitions you do for each exercise.

You'll need someone to go with you to the batting cages once a week to record your speeds. This will allow you to compare the speed of your swing at the beginning of the experiment and the end of the experiment. This is a perfect science fair project to do as a team, if your school allows it. Getting a buddy to do the same experiment will enable you to work together and help each other. Plus, it will make the project a lot more fun.

The control in this experiment will be how far you hit the ball before you begin practicing and working out. You can gauge that by your score at the batting cages.

The variables are the measures you take to increase your strength, and to, hopefully, increase the speed of your swing. At the end of the experiment, you'll see whether you're able to transfer more energy from the bat to the ball, both by using a bigger bat and by swinging faster.

So go ahead and venture a hypothesis of whether or not you'll be hitting better and farther after eight weeks of practice and lifting. What do you think?

Materials You'll Need for This Project

You'll need the following materials for this project:

- A baseball bat

- A baseball

- Access to batting cages that provide an automatic pitching machine and a device that measures the speed of your swing

- Weights, either free weights or a weight machine

- Advice from a trainer or experienced lifter

Conducting Your Experiment

Follow these steps:

- Consult with a trainer and begin a weight-lifting routine that's tailored to your physical strength and condition. Be sure the trainer understands your goal so he or she can suggest specific exercises for you.

- Keep a log of the exercises you'll be doing, the amounts of weight you'll use for each exercise, and the number of repetitions completed for each exercise. You can use the chart found in the next section, "Keeping Track of Your Experiment," if you wish.

- Practice daily at swinging the bat as fast as you can, while still maintaining control.

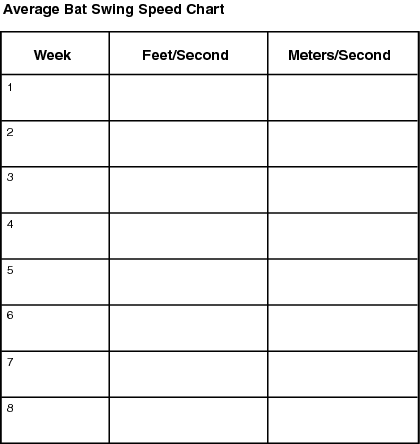

- Once a week, visit the batting cages and record the rate of speed at which you hit the ball.

Keeping Track of Your Experiment

Record your exercise information on these charts, or make your own charts, if you prefer. Be sure to record your information each time you exercise.

Ideally, have someone accompany you to the batting cages and record your speeds. Have your buddy write down all your speeds for that session so that you can calculate the average speed and write it on the chart.

You will need to make charts similar to these for each different exercise in your program.

Use the following charts to keep track of your average bat swing speeds.

Putting It All Together

When you've completed the experiment and recorded all the information, think about how much you improved over the eight-week period. Did you see a difference in muscle mass, speed and batting average? Do you sense that hitting the ball has become more reflexive than it was when you first started the experiment? Are you able to use a heavier bat, which also will increase the amount of energy you're transferring from bat to ball?

If you said yes to the questions above, then you proved several things during the experiment. You proved the equation to be correct-that increased mass and velocity result in increased bat speed, which transfers more energy to the ball. And, you proved that neurological pathways-although they don't occur as readily in teens and adults-can contribute to better hitting.

Further Investigation

If you want to keep working on this idea, you could observe, and possibly interview, really good players at as many levels as possible. Find out how old they were when they began playing, if they follow a workout routine, the weight of the bat they use, their batting averages, and so forth.

Gather as much information as you can, analyze it, and see what patterns you come up with.